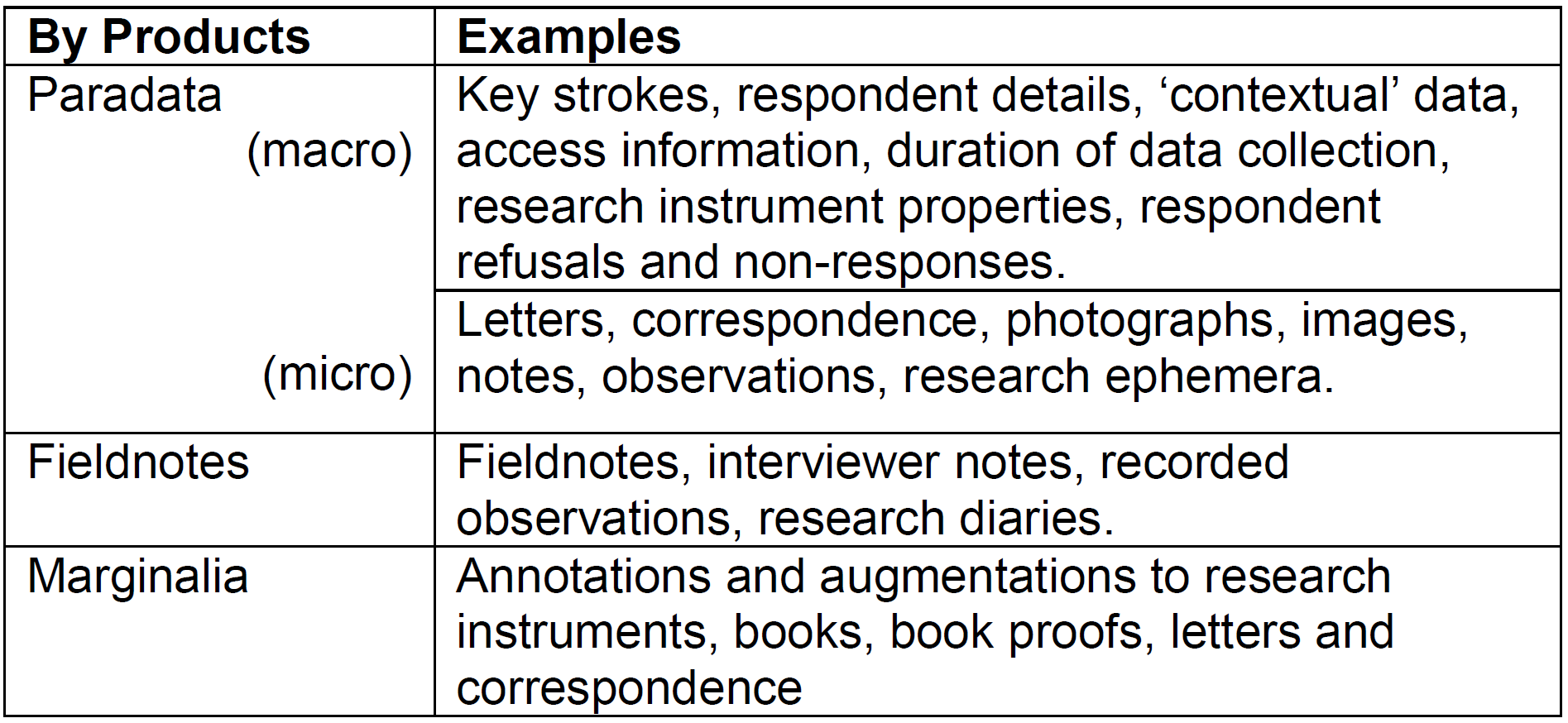

In recent years, methodological innovations have led social science researchers to attend to features of their research beyond the data collected. On the one hand, rising costs and falling response rates have led survey researchers to find ever-more sophisticated ways of understanding and improving survey quality and costs. Towards these ends, the analysis of the macro and micro paradata generated during data collection is becoming well established in the quantitative field. On the other hand, as part of a ‘reflexive turn’, qualitative researchers have developed analyses of fieldnotes in order to better understand how research accounts are co-constructed between researchers and participants. Similarly, in the field of humanities, researchers are focusing on notes marked in the margins of books as a way to illuminate the art of meaning making in reading. By focusing on paradata, marginalia and fieldnotes as ‘by-product’ material of and for social research, we can throw light on their substantial analytical value and the potential to add depth to our understanding of the research process.

By-product materials of and for research can range from brief written calculations, digitally recorded computer keystrokes, extensive pieces of written narrative or digitally recorded verbal exchanges. They have moved from being background shadows of research practice to a place in the spotlight as informative and illuminative in themselves, helping to elucidate the methodological or substantive specificities of a particular period, place, research study and/or person. They point to the normative research and social assumptions of the time.

Relationships are integral to paradata, marginalia and fieldnotes, both constituted through their production and reflected in their study. Researchers pursuing the craft of studying by-product materials are engaging with often-complex sets of relationships. These can include:

Between a field interviewer and their interviewee: The by-products of research point to the relational exchanges that are integral to the collection of data, such as the interactions between interviewers and respondents in the conduct and delivery of survey interviews in the field. Approaching the interview setting as a social interaction that is subject to conversational norms can reveal the necessary relational work that underlies the production of the survey data through the posing and answering of questions.

Between a field interviewer and the core research team: The actual process of data collection may be undertaken by contracted field researchers who then pass that material to the (academic) research team who have designed the study and will analyse the data.

Within research teams: Where research is conducted among teams of people, the by-product communication materials that ‘go along’ with the research process can be revealing of relationships among the team. Intricate webs involving the tense and disputatious as well as creative relations between researchers working together may be evident.

Between the creator of paradata, marginalia or fieldnotes and themselves: There are moments when the by-products of research and reading activities appear to be an analytic commentary in which the creator attempts to explain to themselves how they should understand a situation or argument.

Between a reader of a text and another reader of that text, known or unknown: The creation of marginalia is not just associated with primary practices, but can be a form of secondary practice, such as annotations to a primary text; responses to the text that are created by the reader of that text. In a further layer, they are sometimes not produced (only) as conversation with one’s self in response to reading but composed with other readers in mind and with an eye to posterity.

Reader engagement with writers, material and meaning: Writing in books or notes on interview materials or fieldnotes functions can give analytic insights into the concerns and identities of the writer, as well as how they actively struggle to clarify intended meanings.

Between the creator/s of the paradata, marginalia or fieldnotes and the researchers who analyse it: The by-products of the activities of research and reading are subject to (secondary) analysis by people other than those who created them, who are thereby propelled into some form of relationship with those originators. They have the potential to convey a sense of being at the interview, alongside the survey interviewee and field interviewer who are creating paradata, bridging between the creator and researcher over time.

Paradata, marginalia and fieldnotes are often messy and evocative, reflecting complex structures and operating at multiple levels that deserve and require a sophisticated analytic approach. Their study raises knotty issues around whether or not the study and analysis of these materials ‘fix’ them and/or bring us close to what was actually going on at the time of their creation. Nevertheless, the relationality and multi-dimensionality of by-products are able to make a valuable contribution to research understanding. Studying paradata, marginalia and fieldnotes is so engaging and informative that it can become addictive and a primary focus.

Paradata, Marginalia and Fieldnotes: The Centrality of the By-Products of Social Research, edited by Rosalind Edwards, John Goodwin, Henrietta O’Connor and Ann Phoenix will be published by Edward Elgar in 2017

http://www.e-elgar.com/shop/working-with-paradata-marginalia-and-fieldnotes